Whether you’re recording and producing music, setting up the perfect audiophile system, or putting together a state-of-the-art home theater, aren’t we all after the same thing? A satisfying listening experience? The audiophile understands this and in fact pursues it regularly and passionately making vivid listening experiences a central part of the audiophile life. And anyone who produces music would love an engaged audience – as large as possible – to have vivid listening experiences with their productions.

Whether you’re recording and producing music, setting up the perfect audiophile system, or putting together a state-of-the-art home theater, aren’t we all after the same thing? A satisfying listening experience? The audiophile understands this and in fact pursues it regularly and passionately making vivid listening experiences a central part of the audiophile life. And anyone who produces music would love an engaged audience – as large as possible – to have vivid listening experiences with their productions.

But what are we doing in the listening experience? How do we listen? What are some of the things that affect the experience of listening? Heck, what do we even mean by listening? I know, I know, my philosophy training is showing. But it’s useful to take a more philosophical look at the listening experience, since it’s involved in some of the more profound moments of music-lovers’ lives.

On the more practical side, one of the more common questions I’ve gotten from clients over the years is how to listen to improvements made by installing acoustic treatments. This is worth some audiogeek time to explore. So let’s dive in.

What is The Listening Experience?

To unpack the listening experience, I propose that it requires attention, or the active engagement of our consciousness with the audio being played. Fidelity of the sound is important to the quality of audio experience for both live performance and in sound reproduction/playback. And, the act of listening evokes emotional engagement with the audio. If we are going to understand the listening experience, we must understand these three characteristics.

Pay Attention

It seems obvious that we must pay attention to the audio or music being played, but what do we pay attention to? Listening, as with all forms of perception, is flawed in many ways, plagued with things like expectation bias and placebo effect. While perception in general is notoriously fickle, listening is especially so. There are many reasons for this. One is simple attention; we can be distracted from listening pretty easily. In this regard, listening is no different from any other mode of perception (vision, touch, etc). Other reasons have more to do with the mechanism of hearing itself. One example is the fact that our ears are more sensitive to some frequencies than others, and this imbalance of sensitivity changes at different volumes. These depictions of the variable “frequency response” of human ears are known as the Fletcher Munson curves.

In addition, we can sometimes pay attention to certain parts of the music (say, the bass part or the trumpet), rather than the whole (everything at once). For instance, when we are mixing a kick drum to sound good with the rest of the music, we are focused only on the frequencies where the kick drum is at play (ie, the low end under 400Hz, with the “click” of the drum up at 4-6kHz or so). When we listen in that way, we are totally focused on the kick and the other bass instruments, and other things like the cymbals or background vocals are completely beyond our attention span .

In addition, we can sometimes pay attention to certain parts of the music (say, the bass part or the trumpet), rather than the whole (everything at once). For instance, when we are mixing a kick drum to sound good with the rest of the music, we are focused only on the frequencies where the kick drum is at play (ie, the low end under 400Hz, with the “click” of the drum up at 4-6kHz or so). When we listen in that way, we are totally focused on the kick and the other bass instruments, and other things like the cymbals or background vocals are completely beyond our attention span .

Most casual listeners generally pay attention to either the beat or the groove of the song, and the lead vocals. Some people hear lyrics right away, others listen more to the music before unpacking the lyrics further into the song or on subsequent listens. It’s also possible to listen to the entirety of the song at once, in those gestalt moments where we are able to “zoom out” our consciousness and listen to something, as new, in its entirety.

The point is, regardless of which aspects of the audio we are paying attention to, careful listening requires active engagement from our consciousness. If we aren’t paying attention, then we probably aren’t having much of a listening experience.

Fidelity

There’s no question that, for careful listeners, the fidelity of the audio being played is of primary importance in the listening experience. There is an experiential and qualitative difference between listening to a favorite recording with earbuds on a subway, and listening on a state-of-the-art sound system in an acoustically treated room. However, it’s possible I’m using fidelity in a different way than some. Rather than a low-distortion, full frequency response and dynamic range conception of fidelity, I’m simply meaning anything pleasing to the human ear, which (as any electric guitarist knows) can often include quite a bit of distortion, or lo-fi production techniques.

Fidelity is about setting the stage for the listening experience. A compelling audio performance is seductive in a way, in that it can draw out both our attention and our emotional responses to the music. But a hi-fi recording of a performance is even more seductive in the sense that we are more likely to be drawn into the recording. In the same way, listening to a skilled musician playing live can always be compelling, but if that musician is playing a superior-sounding instrument in a great-sounding room, the odds for a positive listening experience go up.

Fidelity is about setting the stage for the listening experience. A compelling audio performance is seductive in a way, in that it can draw out both our attention and our emotional responses to the music. But a hi-fi recording of a performance is even more seductive in the sense that we are more likely to be drawn into the recording. In the same way, listening to a skilled musician playing live can always be compelling, but if that musician is playing a superior-sounding instrument in a great-sounding room, the odds for a positive listening experience go up.

The quest to maximize fidelity is where we see the “gearhead” phenomenon. It drives the market for a wide variety of products in both the audiophile and recording worlds. Certain products, such as a mic preamplifier or a set of audiophile speakers, can become almost legendary in their sonic characteristics. At the end of the day, most equipment purchases made by both producers and listeners is all about increasing fidelity, to maximize the chance of a positive listening experience.

Of course, acoustic treatment in a listening environment can contribute as much as anything to fidelity. There will be more about treatment below, but one of the big reasons to acoustically treat a room is that it opens the doors for emotional engagement with the music.

Emotional Engagement

And this is the point of music, isn’t it? We’ve all had experiences where we’ve been moved by music in some way, or we wouldn’t be here in the quest for better audio. It’s why we listen to recordings in the first place. It’s why we go to live shows, either to enjoy musicians we love, or to be blown away by an unknown musician’s performance. Psychologists speak of the flow state, and I believe an emotionally engaged, quality listening experience is akin to the “complete absorption in one’s task” we see in flow.

But emotional engagement doesn’t always happen. There are barriers to it. For me, if there are technical problems with the audio it can interfere with the emotional engagement. I remember seeing Jane’s Addiction a few years ago. I was excited to see them, but I knew the theater in question had poor acoustics, with far too much reverb and echo for modern music. And sure enough, there was so much sound swimming around the venue, especially with the loud mix from their PA system, that it was just unbearable. Earplugs took away the physical pain, but the show – and my listening experience – were ruined by the jumbled, swimmy, acoustic mess where nothing was distinct in the music.

But emotional engagement doesn’t always happen. There are barriers to it. For me, if there are technical problems with the audio it can interfere with the emotional engagement. I remember seeing Jane’s Addiction a few years ago. I was excited to see them, but I knew the theater in question had poor acoustics, with far too much reverb and echo for modern music. And sure enough, there was so much sound swimming around the venue, especially with the loud mix from their PA system, that it was just unbearable. Earplugs took away the physical pain, but the show – and my listening experience – were ruined by the jumbled, swimmy, acoustic mess where nothing was distinct in the music.

Being an audiogeek, of course, I immediately think about what an investment in acoustic treatment could have done for that listening experience by bringing the out-of-control reverb down in that room. Theater owners, if your patrons often complain about the sound quality in your venue, give us a call. We can help. And, dramatically lowering reverb – and increasing clarity and intelligibility – in large rooms is one of the more obvious improvements acoustic treatment can make. But let’s take a look at some of the not-so-obvious differences to listen for.

Learning to Listen and Acoustic Treatments

In both the pro audio and audiophile communities, one of the most common questions I’ve gotten from clients over the years is, “Ok, I took your advice and treated my room. I got the treatments installed. Now, when I listen, it sounds…. different. I can’t tell if it’s an improvement. What exactly should I be listening for?” So let’s answer that, going through some of the more common treatment strategies:

-

Bass Trapping. This one is a bit of an enigma because it can profoundly change the listening experience. Many clients are astonished to find that absorbing excess bass in a room can actually make the bass appear louder (by eliminating nulls)! Other times, boomy bass is tamed so the bass is softer than it was. Most likely, a combination of the two will be happening at different frequencies. In short: the bass, whether softer or louder, will be more accurate, with less room ringing which produces the “one note bass” phenomenon. When you pay attention to the bass, you will be able to hear a lot more detail in the performance. Listening to music with masterful bass performances, as opposed to some styles that tend to have root notes and simple harmonies that repeat quite a bit, can help bring this out more.

-

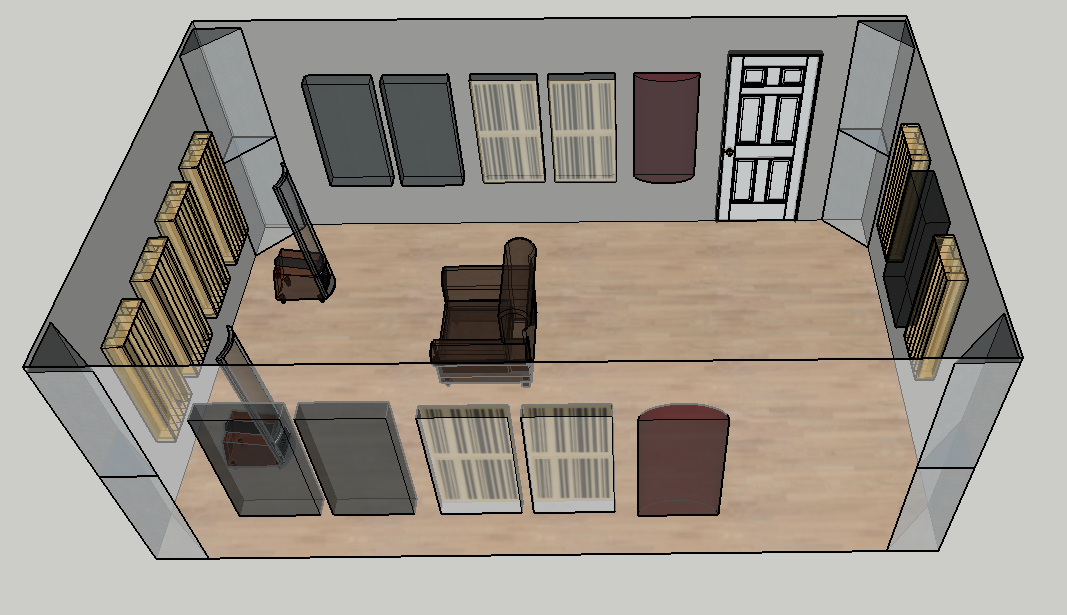

First Reflection Points. When we treat the first-reflection points to create a reflection-free zone at the listening position, the difference can be startling. The first thing we may perceive is that the sound is “dryer” or “deader,” which is to be expected since absorption is by far the most common treatment here. But once our ears adapt to the drier sound, at some point most listeners realize that the soundstage they enjoy is much wider and more detailed, with a more coherent placement of each instrument in the stereo image. Music will have a new clarity, not unlike that of headphones, but with all the benefits of a great set of speakers. Listening to music with wide stereo imaging, such as a good live recording of classical or jazz music, as well as a lot of acoustic music with several different instruments playing in the same frequency ranges as one another can make the differences easier to hear.

-

Rear Wall Treatments. Typically this involves two aspects: first is bass response, second is the overall ambiance or sense of space in the music. Most often, there is at least one big peak and one big null related to the length of the room, so thick bass trapping on the rear wall will help flatten those out. The difference is more subtle overall than extensive corner bass trapping, but rear wall treatments are likely to make a big difference in one or two frequency ranges that were problematic. And, putting diffusion into the mix, such as with our Alpha 6As, will increase the ambiance of the space by keeping the diffused high frequency energy in the room. Listening to music that is rhythmic and staccato can help bring out the decay time of the room.

For listening experiments with new acoustic treatment installations, it is best to stick with music that is well-recorded, masterfully mixed, and above all, very familiar to you. It’s not uncommon for listeners in newly-treated rooms to report that they can now hear some subtle detail they’ve never heard before. Treating a room is like lifting a veil off the sound; everything is more immediate, more coherent, with less barriers between the music and a quality listening experience.

Often, beginning engineers have trouble discerning some of the subtle changes required to get a mix sounding good. Difficulty in discernment is certainly a function of experience, practice, and training, but it is also a function of the accuracy of the listening environment. And in my experience it’s quite easy to conflate the two.

Earlier in my career I was doing a lot of mixing in an unfinished, untreated basement. The floor and walls were concrete, and the ceiling was wood joists with the subflooring above visible from the basement. In other words, pretty much all surfaces in the room were reflective. With no acoustic treatment, needless to say what I heard coming from my speakers in that room was a jumbled mess. Is it any wonder I had difficulty hearing subtle EQ tweaks in the midrange, or precise panning, or reverb & delay tails?

Then, in the quest to make better audio, I finally discovered acoustic treatment, and installed some rudimentary treatments to improve the sound in the room. As I’ve written before, this was a definite “light-bulb moment” for me, both in terms of the quality of my tracks recorded in that room going up dramatically, but also in my confidence as a mix engineer. The difficulty in discernment I’d be experiencing wasn’t due to my lack of experience, or lack of ability to hear, it was because of the acoustics in my listening room! Once I treated the space, now I could hear all these changes I had been seeking and reading about. The importance of this ear-opening experience cannot be overstated, and the best advice I can give to beginning engineers is to be very careful about the listening environment.

All this applies to audiophiles as well. Though it can be argued that audiophiles listen differently than engineers do, there are certainly experienced audiophiles who have very discerning ears, capable of hearing similar detail to an engineer. But regardless of the way in which we practice critical listening, acoustic treatment can help us.

When In Doubt, Ask For Help

As always, we are happy to help you strategize about how to maximize your listening experiences using patented GIK Acoustic treatments. Contact us for free acoustical advice.

GIK Giveaway Viral Video Contest 2024

Room EQ Wizard TUTORIAL

How to set up and use REW In this video we show you how [...]

DIFFUSION Concepts Explained

How Acoustic Diffusers Work And Which One Is Right For You In this video [...]

Jan

The GIK Acoustic Advice

Get Your Room Sound Right For FREE! In this video we are giving a [...]

Jan

Designer Tips: The Significance of “Clouds” with Mike Major

When people reach out to us at GIK for acoustic advice, we never have any [...]

Jun

Designer Tips: The Importance of Coverage Area with James Lindenschmidt

The most important factor in acoustic treatment performance is coverage area. Or more specifically, the [...]

May

Designer Tips: Home Theaters and Acoustic Balance with John Dykstra

Without fail, one of the first things our clients say to us when we begin [...]

May

Summer Giveaway 2021 Vote

The GIK Acoustics Summer Giveaway Photo Contest 2021 invited customers to submit photos illustrating how [...]

Aug